David R. McClay Awarded 2016

Developmental Biology-Society for

Developmental Biology Lifetime Achievement Award

By Marsha E. Lucas

David

R. McClay, Jr., the Arthur S. Pearse Professor

of Biology at Duke University, received the 2016

Developmental Biology-Society for

Developmental Biology Lifetime Achievement Award

for his outstanding and sustained research and

mentoring contributions to the field of

developmental biology. McClay is being recognized

for his distinguished body of work uncovering the

mechanisms underlying cell fate specification,

patterning, and morphogenesis in the sea urchin

embryo. His discovery that nuclear β-catenin

specifies vegetal fates proved to be of great

significance as it is critical for endoderm

specification in numerous vertebrate and

invertebrate species. His group established the role

of Notch signaling in secondary mesenchyme induction

and has been a leader in unpacking sea urchin gene

regulatory networks. David

R. McClay, Jr., the Arthur S. Pearse Professor

of Biology at Duke University, received the 2016

Developmental Biology-Society for

Developmental Biology Lifetime Achievement Award

for his outstanding and sustained research and

mentoring contributions to the field of

developmental biology. McClay is being recognized

for his distinguished body of work uncovering the

mechanisms underlying cell fate specification,

patterning, and morphogenesis in the sea urchin

embryo. His discovery that nuclear β-catenin

specifies vegetal fates proved to be of great

significance as it is critical for endoderm

specification in numerous vertebrate and

invertebrate species. His group established the role

of Notch signaling in secondary mesenchyme induction

and has been a leader in unpacking sea urchin gene

regulatory networks.

McClay earned his Bachelor’s degree in zoology at

Penn State University in 1963 and his Master’s

degree in zoology at the University of Vermont in

1965.

However, it wasn’t until he was a graduate student

at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (UNC),

that he was first introduced to sea urchins. McClay

took an embryology course at the Bermuda Biological

Station (now the

Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences) the summer

after his first year of graduate school.

“We collected out in the reef everyday and went

diving and snorkeling for animals,” he said in a

July interview. “I came back from that experience

and decided that Bermuda was a great place to do

research. So, I dreamed up a problem and managed to

do much of my doctoral research in Bermuda.”

McClay studied cell adhesion in sponges under the

mentorship of his graduate advisor, H. Eugene

Lehman. “Gene Lehman at Chapel Hill was wonderful,

and at 96 remains wonderful to my life,” he said.

McClay graduated from UNC in 1971 and headed to the

University of Chicago to do a postdoc with

Aron A. Moscona. There, he began working on cell

adhesion in chick and mouse embryos. Within five

months, McClay had an offer from Duke University to

become a faculty member in the Department of

Zoology. The work he carried out in the mouse and

chick earned him his first grants as an independent

investigator. They were not, however, the only

biological systems on his mind.

“When I got to Duke, I decided that at least a small

part of my research would be looking at the sea

urchin embryo because it’s so simple and perfect for

an experimental embryologist like me,” McClay said.

Sea urchin embryos are transparent, develop rapidly,

and are easy to manipulate, he said. “You can ask a

lot of questions. And because their rate of

development is so fast, you can get answers fairly

quickly.”

What started out as a summer project took over his

entire lab and in 1980, McClay was awarded his first

NIH grant to study sea urchin development. Some

thirty-six years later, he still has that sea urchin

grant.

McClay has been described as “THE world’s expert in

manipulation of living sea urchin embryos.” He says

this came about primarily as a defense mechanism. At

Duke, he was teaching, running a lab, serving on

study sections, and taking on more administrative

responsibilities.

“Life is full of choices and my choice was I did not

want to vacate the laboratory. I decided to look

around and try to figure out what I could do that

would be useful to the laboratory that no one else

in the lab was really interested in doing. I took on

the objective of doing microsurgery and I’ve just

gradually become better and better at it. ... I’m in

there [almost] everyday ... and it allows me to

collaborate on every project with students.”

McClay has trained nearly 6o graduate students and

postdocs in his long career. When asked about his

mentoring philosophy, he said, “There’s no single

formula for doing it. But, I try to work with

students in such a way that allows them to identify

their strengths—and go with them. I don’t know how

good I am, but my students have been pretty darn

successful. So, I’m proud of them all.”

Since his days as a graduate student, McClay has

rarely been home during the summer. He continued to

go to Bermuda up until the mid-1980’s when it became

more important to have time with his children. The

Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole offered a

much more family-friendly opportunity. In 1989, he

became an instructor in the MBL Embryology course

and co-director of the course with Eric Davidson and

Michael Levine from 1991-1996.

McClay now spends his summers in the South of France

at the

Villefranche-sur-mer Developmental Biology

Laboratory located within the Marine Observatory

at Villefranche-sur-mer.

“They’ve been very gracious in allowing me a little

bit of space to set up and do my work,” he said.

|

|

|

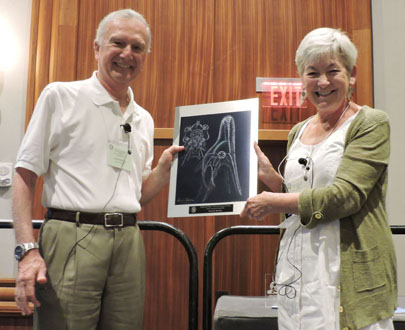

McClay receiving Lifetime Achievement

Award from SDB President-elect, Blanche

Capel at the 75th SDB Annual Meeting in

Boston, MA. |

Interestingly, the work he is doing in France is

based on work first discovered by

Theodor

Boveri (co-discover of the chromosomal theory of

heredity along with

Walter

Sutton). Boveri, while visiting Villefranche in

1901, discovered that the

Paracentrotus sea urchin egg has a

pigment band that surrounds it below the equator

separating the animal and vegetal poles of the egg.

McClay wants to understand how those initial

asymmetries in the egg are established.

“For a long time, we were building gene regulatory

networks along with Eric Davidson’s lab and other

members of the sea urchin community. And, for me,

the whole rationale behind that was to allow us to

identify transcription factors that drive specific

processes in development. And that’s mostly what I

do, to look at what drives gastrulation, what drives

different cell movements. But, I was always puzzled

because... the gene regulatory network we were

working with started at the 16-cell stage. But, you

know there’s something there earlier.”

It is now known that “the vegetal area of the egg

harbors factors that are necessary for specification

of endomesoderm and the animal pole region harbors

factors that are necessary for part of neurogenesis,”

he said.

McClay has learned that you can chop off portions of

the egg, and as long as it has a nucleus, it will

develop. If he cuts off the egg below the pigment

band, cells will divide and divide, but won’t make

endomesoderm. As a result, he now has an assay where

he can add specific maternal factors back to try to

rescue endomesoderm.

“So it turns out,” he said, “if you add back members

of the Wnt pathway, you can rescue endomesoderm. If

you add back, one of the Wnts, you can rescue

endoderm.” He has done this experiment with the

animal pole as well and been able to rescue neurons

by adding back certain not-yet-published maternal

components.

When asked about his most significant discovery to

date, McClay said it is the discovery he’s going to

make tomorrow. “The size of [the discovery] isn’t so

important, it’s just finding something new.”

His scientific journey has not been a solo endeavor.

He expressed his gratitude for several individuals

in his life.

“I very much appreciated

Eric Davidson because he not only was brilliant

and stimulating, but he was a provocateur. I mean,

he would provoke you—make you angry. But, you would

constantly try to say, ‘I’ll show that guy.’ So,

while he was a good friend, he was also a great

provocateur. Eric was important. Another person that

was really important was

John Trinkaus at Yale who when I was younger,

was really terrific in encouraging me and applauding

the efforts that I was putting into looking at

morphogenesis, which is what I’ve been interested in

all my life.”

McClay is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts

and Sciences. He served as SDB President from

1992-1993 and SDB Treasurer from 2003-2004. He

continues to serve as an instructor for the MBL

Embryology Course, as well as director for the MBL

Gene Regulatory Networks Course. He reflected on

being awarded the DB-SDB Lifetime Achievement

Award.

“It’s an award that really is earned by the students

of somebody who’s been in the business as long as I

have because they are the ones who over the years

have produced most of the work. And so, I tell

people that, and yet they say, oh come on, you’re

just deflecting. But, I’m not. It’s true.”

“...Getting an award like this means that you

haven’t done everything in a complete vacuum. And

that’s nice. I’d like to think that what I’ve done

has been relevant and useful in advancing knowledge.

And to get an award like this means that some other

people are in agreement and that to me means a lot.”

|